CORPORATE TAX RATE: The Benefits of Raising Rates Outweigh the Negatives

The Benefits of Raising the Corporate Income Tax Rate Outweigh the Negatives

President Biden wants to increase the corporate income tax rate to 28%. My advice to him and Congress is that we should do it. For over a year, the United States has suffered an economic crisis due to a pandemic. Increasing tax revenue will allow the government to fund initiatives and programs to help the country regain economic balance. A 7% rise in the corporate income tax rate is a modest jump that will result in a significant revenue contribution.

The main objection to corporate income taxes these days is that corporate income tax discourages capital investment and results in fewer jobs. While economic theory suggests that corporate income tax hinders investment in corporations, this impact is one part of the bigger tax picture.

Corporate Income Tax Rates Over the Years

Since 2017, the corporate income tax rate has been a flat 21%, but historically, it has been much higher. Tiered income tax rates were introduced in the 1940s, with some brackets being as high as 53%. For most of the 1980s, the top corporate income rate was 46%. From 1994 to 2017, the rates imposed on corporate income taxes ranged from 15% on the first $50,000 of taxable income to 35% for taxable income over $18,333,333.

The current flat rate is a radical departure from how the U.S. taxed corporate income in the prior 80 years. 21% is 14 points lower than the previous higher rate. An increase of half that to 28% is not even a return to the pre-2018 rates. In fact, overall revenue from such an increase is projected to be slightly lower than revenue collected under the old rates, indicating a slightly lower impact.

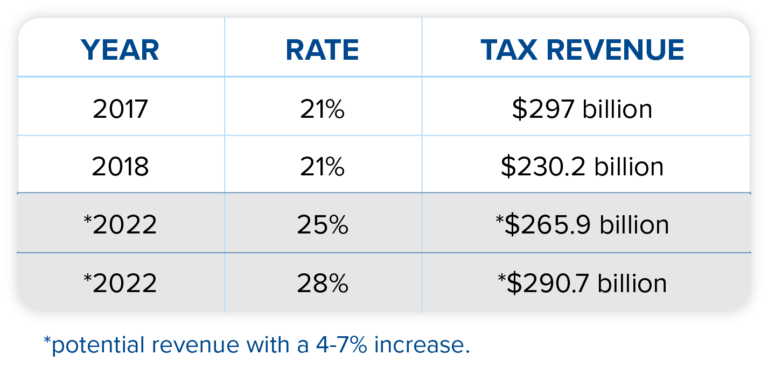

Corporate Income Tax Revenue

Corporate income tax has historically been the third-largest source of tax revenue, after individual income taxes and social security taxes. In 2017, corporate income tax revenue was $297 billion. In 2019, it was $230.2 billion.

If the corporate rate were raised to 25%, the corporate tax revenue estimate for 2022 is $265.9 billion. If the corporate rate is raised to 28%, estimates put 2022 corporate income tax revenue at $290.7 billion, roughly where the revenue was before the 2018 rate change. Increasing the current tax rate to 28% would raise revenue, but that revenue amount would be on par or slightly lower than the revenue raised under the old corporate income tax rate tiered system.

Small businesses won’t enjoy a lower rate, but the revenue effect would be in line with decades of federal budget planning. In fact, I would recommend Biden enact an additional lower rate for small businesses–with the threshold being much lower than $18 million. This would reduce the tax revenue collected but would help small businesses that have managed to stay afloat during the pandemic and renew investment in small businesses.

Measuring Corporate Income Tax Burden

Arguably, an increased rate would put U.S. corporations back where they were before 2018 but is there a larger economic trade-off to such an increase? As I noted earlier, economic theory shows that income tax rates can negatively impact capital investment.

Economists commonly use three metrics to determine the burden of corporate income tax:

The average rate looks at the corporate income tax burden on corporations. It does not look at the statutory tax rates; it is a ratio of income taxes actually paid over corporate revenue.

The second metric is the effective marginal income tax rate. The formula for this metric looks at how the statutory tax rate affects the expected return from investing in a corporate entity or buying corporate shares. The effective marginal tax rate in this formula is the difference between:

- the before-tax real rate of return, and

- the real after-tax rate of return.

The real after-tax rate of return is the money a corporate investor puts in their pocket after tax is paid.

A third metric is the effective marginal income tax rate on capital. This formula also determines the burden of tax on capital available for investment, but it looks at whether corporations are an attractive investment for individuals as compared to other investments, such as real estate, partnerships and LLCs. It accounts for tax rates on various types of investment income, such as capital gains.

The Effect of the Corporate Income Tax Burden

Use of the second and third metric became popular in the last 10 to 15 years. These two metrics look at how the corporate income tax rate burdens “capital” or the shareholders and potential investors. (A general equilibrium model was generally used before, starting in the 1960s.) Applying these metrics show that corporate income tax also burdens labor income–the difference being to what extent.

The effective marginal tax rate formula, used by The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), indicates that the burden on labor income lies between 15% and 40%. The CBO applies a 25% burden to labor income in its computations, the remaining 75% being a burden to capital investors.

An application of this third, and broader formula puts 50% of the corporate income tax burden on labor income and 50% on capital investors.

Economic Trade-offs for Raising Corporate Tax Rates

Back to our question: what is the economic trade-off for the revenue generated by a 7% increase to the corporate income tax rate?

The economic formulas tell us that trade-offs for raising the corporate tax rate is lower wages or loss of jobs and less individual investment in corporations.

In his tax plan, Biden proposes several changes to increase domestic jobs by removing corporations’ incentives to offshore jobs.

To incentivize domestic job creation, Biden would disallow deductions for expenses incurred in hiring employees abroad and give tax credits for hiring U.S. employees. He also would repeal deductions for corporations whose foreign earnings constitute global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). These changes would de-incentivize corporations from moving profitable intangible assets and jobs that support them abroad.

Even if individuals do invest less capital in corporations due to a rate increase, the result should be more domestic capital investment overall.

I posit that a quick injection of cash through government contracts that will improve public infrastructure and prepare for domestic technological growth makes more sense than waiting for the growth that results from keeping corporate tax costs down. Also, government contracts make more for jobs.

Lisa Lopata is an editor and tax analyst for Expandopedia.com. After getting a B.A. in English, Lisa wrote about real estate and tax law for a publishing company. She attended law school, graduating in 2001, and went into practice with a global law firm focusing on international tax planning for Fortune 50 corporations. After years of advising companies on lowering their global effective tax rate, Lisa shifted her career back to writing, this time focusing on state and federal tax law. Recently, Lisa took her position with Expandopedia.com, letting her refocus on U.S. international and foreign tax and corporate laws.