You Say Yes, I Say No – I Say High, You Say Low : Corporate Tax Reform Debate Continues

Should five percent appear too small Be thankful I don’t take it all

’Cause I’m the taxman -The Beatles, Taxman

While The Beatles were apparently united in their opposition to the U.K.’s progressive income tax regime in 1966 (I wasn’t there), the corporate tax reform debate continues today on Capitol Hill. Lawmakers, economists, and tax experts alike have varying conclusions about the magic methodology and the overall impact of increasing U.S. corporate taxes.

Generally, the current political climate surrounding the debate looks something like this:

- President Joe Biden has proposed increasing the corporate income tax rate from 21 to 28%;

- Democratic lawmakers have called for an increase from anywhere between 25 and 28 %; and

- Congressional Republicans have stated that undoing the 21% rate enacted under their signature 2017 tax reform law known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) (P.L. 115-97) is a nonstarter.

Adding to the debate is the Biden administration’s proposed multi-layered approach to corporate and international tax reform, which could make an overly complicated tax code more complex. Long story short, it is quite possible this next year will look a lot like tax reform in 2017 with a subsequent flurry of exciting (let’s be honest – confusing) regulations to follow.

The Long and Winding Road

Before we go down the long and winding road ahead, let’s take a quick look at how we got here. Currently, the U.S. statutory corporate income tax rate sits at 21%, down from 35%, as enacted under the TCJA, eliminating the prior four-step graduated corporate rate structure. Along with the significant rate decrease, the TCJA provided for several other base-broadening (and reducing) changes, such as full expensing for investment in short-lived assets through 2022 as well as a repeal of the corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT).

Generally, for C corporations, the income tax liability occurs at the entity level on its gross income, less allowable deductions, before shareholders receive income as dividends or capital gains, which is then taxed again at the individual level once distributed. “When accounting for both levels of tax, under current law, corporate income faces a combined top tax rate of 47.47%, reduced from a pre-TCJA rate of 56.33%,” according to the Tax Foundation.

However, there are circumstances when double taxation does not occur, as many shareholders of corporate stock, such as retirement accounts and educational institutions, are exempt from income tax.[1]

Biden Administration Eyes Corporate Income Tax Hike

The Biden administration, on April 7, issued its Made in America Tax Plan Report, which proposes raising the corporate income tax rate from 21 to 28% along with a new 15% minimum tax on the “book income” (earnings publicly reported on financial statements) of certain large corporations. President Biden’s proposed tax plan is intended to fund and accompany a $3 trillion infrastructure package known as the American Jobs Plan.

While the minimum tax on book income is not an inherently new idea, it has its “fair share” (no pun intended) of bipartisan critics. Quite simply because it is not simple at all, and such a tax is intrinsically difficult to implement (as though that’s ever stopped Congress before). Of course, adding to the elixirs at that minimum tax party would be the unchecked authority bestowed upon the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) with its inevitable necessary changes to the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) governing book income, which would now be tied to federal revenue governed by the IRS.

Let’s Talk About Rates

Along with most critics of increasing the corporate income tax rate, I share the concern that a higher rate will impose a higher tax burden on investment in the U.S. and increase the incentive to shift profits and jobs to lower-tax jurisdictions. Although I am certainly not embracing the more dramatic side of that argument that the result would be disastrous, it is simply not ideal from a growth standpoint.

“Raising the corporate tax rate will have far broader implications than taxing the 55 large profitable corporations that allegedly paid no [income] tax in 2020,” Paul H. Kupiec, resident scholar at American Enterprise Institute (AEI) argues. “According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2017 — the last business census available — there were 943,354 corporations in the U.S., most of them small businesses.” Kupiec argues that because corporate profits are generally subject to double taxation, the total tax paid on a dollar of corporate revenue distributed in the form of qualified dividends could reach 45% under Biden’s tax plan.

While increasing the corporate income tax rate is no doubt a “pay-for” to finance other important government projects, the administration also considers it as a means for making up the decline in corporate revenue since the TCJA became law. Corporate tax revenues dropped $67 billion following the TCJA, from $297 billion in 2017 to $230 billion in 2019. However, it is worth noting that corporate investment increased by $198 billion — nearly three times as much as the loss in revenue over that same period.[2]

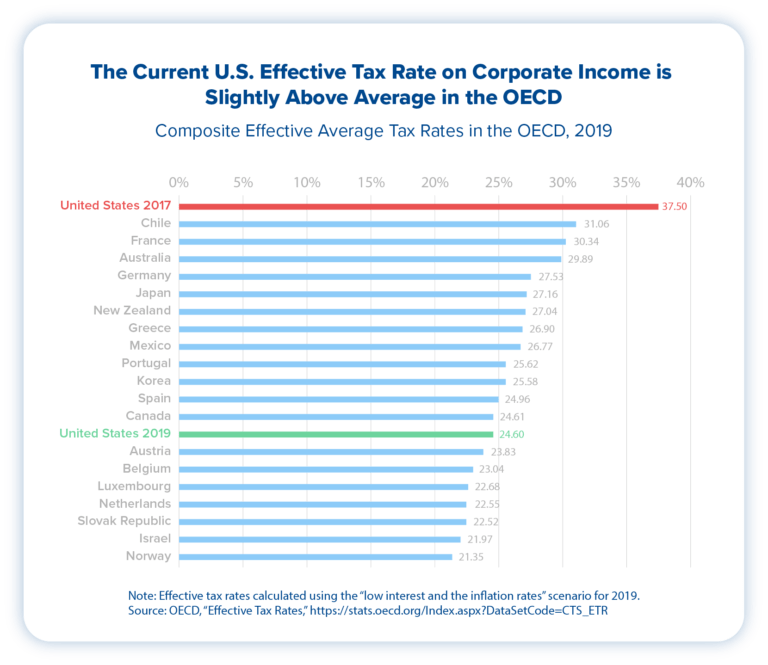

When comparing the tax burden on corporate investment, a frequently used measure is the marginal effective tax rate (METR), which shows how corporate taxes impact investment incentives. This “forward-looking” method measures how taxation increases the cost of investments that return just enough profit to break even in real terms. In 2019, the OECD held that the U.S. had a composite METR of about 11.2%, higher than the non-U.S. OECD average of 7.2% and ranked 17th highest out of 37 countries. Before the TCJA, the U.S. METR in 2017 was among the top 10 in the OECD at 17.4%.[3]

Additionally, Kyle Pomerleau, resident fellow at AEI, stresses the importance of providing an accurate look at the effective tax burden on corporations and criticizes the Biden administration for not doing so. The Biden administration, arguing in favor of its corporate tax increase, claimed that the U.S. would raise less revenue from corporations as a percentage of GDP than our trading partners. This talking point, however, is disingenuous, according to Pomerleau. “Comparing corporate revenue collections as a percent of GDP without accounting for differences in the size of the corporate sector is misleading,” he said.

Ultimately, whether corporate tax collections as a portion of GDP, average effective tax rates, or marginal tax rates are used, each measure shows that the U.S. effective corporate tax burden is near or above the average compared to other OECD nations, according to economists Daniel Bunn and Garrett Watson. “Raising corporate income taxes would put the U.S. at a competitive disadvantage, whether one looks at statutory tax rates or effective corporate tax rates,” Bunn and Watson note.[4]

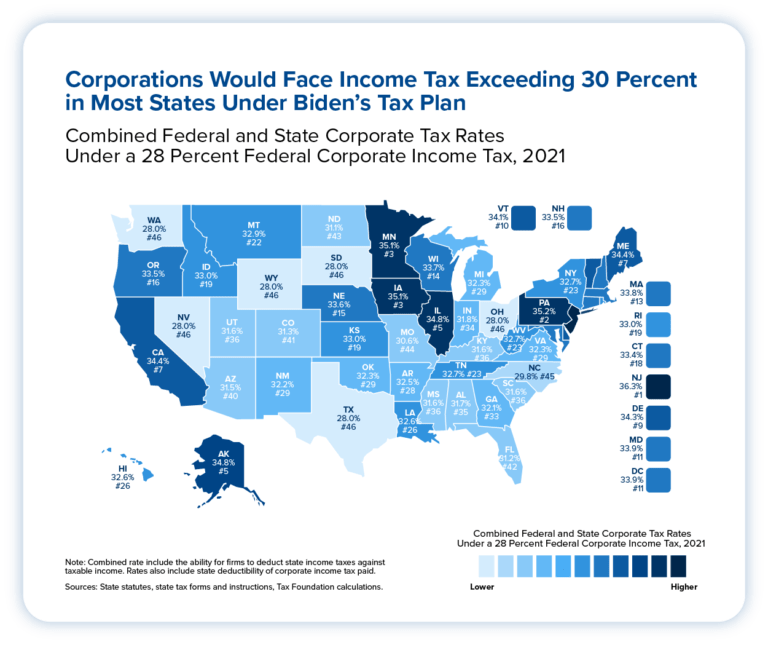

Further, economists have stressed the importance of considering the impact of state and local taxes when analyzing the effect Biden’s proposed 28% corporate income tax rate will have upon competitiveness. Under Biden’s proposal, corporations in 32 states and Washington, D.C., would face a corporate tax rate of approximately 32% – the highest among OECD nations.[5]

“The economic literature shows that corporate income taxes are one of the most harmful tax types for economic growth, as capital investment is sensitive to corporate taxation, … [which] lowers long-run economic output, reducing wages and living standards,” a February 2021 Tax Foundation report states. However, to be both fair and accurate, an analysis of growth and investment in relation to the corporate income tax rate needs to include other potential domestic policy incentives, which currently remain uncertain under Biden’s tax plan.

The Made in America Tax Plan does imply that it aims to temper the sting of the rate increase with new or enhanced tax breaks such as “generous incentives for research and development” (R&D) and “clean energy production,” and also alludes to eliminating incentives for fossil fuels. Thus, the details of such tax breaks and their effect on corporate tax reform remain to be seen.

Evaluating Corporate Tax Incidence

When evaluating the incidence of corporate income taxes, it is essential to remember that a chain reaction occurs affecting shareholders, workers, and consumers. Regardless of political leanings, economists broadly agree that corporate income taxes impact workers and wages. How much, however, is up for debate.

While the programs that proposed Democratic corporate tax hikes are intended to finance may indeed be worthwhile, I, as well as most economists, contend with certainty that raising the corporate income tax rate has consequences that reach beyond the entity. Thus, the debate is not so much on the existence of such consequences; rather, it is on the breadth and depth of the impact.

“Shareholders bear some of the corporate income tax burden, but they aren’t the only ones,” the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) states. “In calculating distributional effects, the [TPC] assumes investment returns (dividends, interest, capital gains, etc.) bear 80% of the burden, with wages and other labor income carrying the remaining 20%.”

However, a 2020 working paper out of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) states that many economic analyses often underestimate the impact corporate income taxes have on consumers.[6] In a unique study of corporate taxes and retail prices, it was found that when taking into consideration product prices, the burden distribution is as follows:

- Consumers – 31%;

- Workers – 38%; and

- Shareholders – 31%.

“Approximately 31% of corporate tax incidence falls on consumers, suggesting that models used by policymakers significantly underestimate the incidence of corporate taxes on consumers,” the authors state.

Corporate Rate Hike Phase-In May Be Worse

While a corporate rate hike this year appears likely, some supporters have proposed a seemingly middle- ground offering of phasing in the tax hike gradually. Indeed, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen herself has said that any corporate tax increases would be phased-in slowly over time. Although the theoretical underpinnings of a gradual introduction to raising corporate taxes are certainly understandable, I would caution against such a strategy. Phasing in a corporate rate increase, rather than allowing it to become effective immediately upon enactment, may be worse for financial planning and investment purposes.

“A corporate tax rate increase will inflict immediate economic harm even if its implementation is delayed,” Kyle Pomerleau has said.[7] “Firms are forward-looking, basing their investment decisions on projected revenues and costs over the life of a potential investment project. If Congress has scheduled a future corporate income tax rate hike, firms will incorporate the rate hike into their investment decisions today.”

Undoubtedly, such significant reforms to corporate tax law would have an immediate effect on a company’s financial earnings statements and investments, regardless of whether they were phased in over time. Further, a delayed corporate income tax increase could not only cause a delay in new investments, but it would also essentially reward old investments while discouraging or penalizing new ones.

Democrats Poised to Peel Back GILTI/FDII Carrot-and-Stick Taxation of Mobile Income

The Biden administration and top Democratic tax writers are also poised to peel back the carrot-and-stick approach used for taxation of income from mobile capital. Biden has proposed nearly double the minimum tax on foreign profits of U.S. companies to 21% and would remove the available exclusion equal to 10% of qualified business asset investment (QBAI).

Currently, the U.S. has a 10.5% minimum tax on foreign earnings (Global Intangible Low- Taxed Income or GILTI), housed in Code Sec. 951A enacted under the TCJA. The GILTI regime was adopted as an anti-abuse rule to deter companies from shifting intangible assets to low-tax jurisdictions.

Accordingly, Biden also proposes repealing the “carrot” to the GILTI “stick,” known as the Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII) regime. Under current law’s carrot-and-stick approach, the FDII acts as a parallel policy for “mobile income.” The FDII regime is intended to balance the GILTI regime and encourage U.S. multinationals to retain mobile income generated from the supply of goods, services, or intangible property in the U.S.

Generally, economic literature shows that the combination of the GILTI/FDII regime, while not necessarily perfect, makes the U.S. more attractive for investment. “The reactions of foreign governments and commentators to the international tax provisions of the TCJA suggest that these provisions (together with the lower corporate tax rate) make the [U.S.] more competitive for investment,” economists wrote in the Columbia Journal of Tax Law.[8]

However, the Senate’s top Democratic tax writer, Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, D-Ore., recently unveiled his Overhauling International Taxation framework, which is vehemently opposed to the TCJA’s GILTI/FDII regime as currently enacted. “This system needs significant reforms to ensure big corporations pay their fair share, while helping to spur investment in the U.S., not in foreign countries,” the framework states. “If FDII remains, regardless of what the final GILTI and FDII rates are, those rates should be equalized.”

The BEAT Goes On (Until it Doesn’t)

Further, the administration, which may have a thing against Sunny and Cher’s hit “The Beat Goes On” (la-de-da-de-da) – okay, that’s unlikely – proposes a repeal-and-replace of the TCJA’s 10% base erosion and anti-abuse tax known as “BEAT.” Generally, the BEAT is a 10% minimum tax (through 2025) that is imposed to prevent foreign and domestic corporations operating in the U.S. from avoiding domestic tax liability by shifting profits out of the U.S. Under current law, the BEAT goes on to 12.5% in 2026.

In its place, the administration proposes “SHIELD” (Stopping Harmful Inversions and Ending Low-tax Developments), which would deny multinational corporations U.S. tax deductions by reference to payments made to related parties that are subject to a low effective rate of tax.

Replacing the BEAT would incentivize other “large economies to join the U.S. in taking the first step to adopt strong minimum taxes on corporations and leveling the playing field between the taxation of domestic and foreign corporations,” according to Treasury.

Two to Tango: U.S. Corporate Taxes, OECD Negotiations

Looking ahead, the Biden administration may be intending to create a bit of a dance between U.S. corporate tax policy and ongoing international negotiations with the OECD. Indeed, Yellen, during her January confirmation hearing, alluded to such a Tango in which OECD negotiations and corporate tax reform could be cheek-to-cheek.

“We look forward to actively working with other countries through the OECD negotiations to try to stop what has been a destructive global race to the bottom on corporate taxation,” Yellen said. “In that context, we would ensure the competitiveness of American corporations even with a somewhat higher corporate tax rate.”

Generally, this would create a new, heightened connection between the OECD debate and U.S. domestic tax policy, according to international tax policy correspondent Alex Parker.[9] Likewise, Barbara Angus, former House Ways and Means Committee chief tax counsel and current global tax policy leader for Ernst & Young (EY), too, recognized the possible new interplay. “I don’t think we’ve seen that intertwining before,” Angus said.

Essentially, this interaction could allow the Biden administration to raise U.S. corporate taxes while working to create more strenuous global tax rules to hopefully reduce the domestic corporate tax hikes’ effect on global competitiveness. “Together, we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations, and spurs innovation, growth, and prosperity,” Yellen said.

Angus calls this “new turf” for the OECD. “The design of your tax system, where you want to set your corporate tax rate, the extent to which you want the funding of your government to rely on corporate taxes versus other types of taxes — these are all pretty fundamental sovereign choices.”

Come Together

Speculation of possible changes to domestic and international tax policy aside, what is absolutely certain about the corporate tax reform discussion is that there is no active legislative language to review or evaluate. And once such legislative text becomes available, even those policies and their combined effect are subject to change.

However, we know that Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.V., a key swing vote in the upper chamber, favors a 25% corporate income tax rate. We also know that moderate Republican Sen. Susan Collins, R-Me., known for her record of bipartisanship, has alluded she will not vote in favor of a 28% corporate tax rate. “I won’t support American businesses paying the highest corporate tax rate among developed countries in the world once again, and, unfortunately, that’s what 28% would be,” Collins said on May 2. “And that means that jobs would once again go overseas,” she added.

Ideally, bipartisanship should always be the goal with far-reaching legislation, which under regular order requires a 60-vote threshold in the Senate. Even if Democrats and Republicans cannot come together in agreement about the taxation of corporate entities, Democratic leadership will still have to work hard amongst its slim majority to reach intraparty consensus on any tax reform proposal. To that end, the budget reconciliation process is the likely vehicle for Biden’s tax plan. Although reconciliation requires only a simple majority to pass legislation (as seen with the TCJA), it has certain budgetary limitations. The narrow hold Democrats have in both chambers means that successful passage of Biden’s tax agenda requires finding common ground among the Party’s deficit hawks.

“Try to see it my way…” Perhaps, negotiations on Capitol Hill are best accompanied by The Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out.”

[1] Tax Policy Center Briefing Book (May 2020).

[2] Alex Durante and William McBride, Corporate Investment Outweighs Federal Revenue Losses Since TCJA, Tax Foundation, (April 22, 2021).

[3] Daniel Bunn and Garrett Watson, U.S. Effective Corporate Tax Rate is Right in Line With Its OECD Peers, Tax Foundation, (April 2, 2021).

[4] Id.

[5] Garrett Watson, Combined Corporate Rates Would Exceed 30 Percent in Most States Under Biden’s Tax Plan, Tax Foundation, (April 1, 2021).

[6] Scott R. Baker, Stephen Teng Sun and Constantine Yannelis, Corporate Taxes and Retail Prices (NBER, Working Paper No. w27058, 2020)

[7] Kyle Pomerleau, Problems With Delaying a Corporate Rate Increase, AEI, (March 5, 2021).

[8] Singh, K., & Mathur, A. (2019). THE IMPACT OF GILTI AND FDII ON THE INVESTMENT LOCATION CHOICE OF U.S. MULTINATIONALS. Columbia Journal of Tax Law, 10(2), 199–224.

[9] Alex Parker, “Biden’s Bid to Refocus Global Tax Pact Comes With Risk,” Law360, (April 9, 2021).

As Western CPE’s VP of Tax Policy and Strategic Partnerships, Jessica keeps her finger on the pulse of Congress and the IRS. She has an extensive background in analyzing and writing on issues related to federal tax policy and IRS administration and has regularly attended congressional hearings and markups on Capitol Hill, as well as public hearings at IRS headquarters. Jessica’s legislative and regulatory procedural knowledge, coupled with her tax law expertise, make her well-versed in the complex worlds of tax policy and administration.

Before her years analyzing tax law with Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting (CCH) and Bloomberg BNA, Jessica represented taxpayers in a wide range of matters before the IRS. Immediately prior to joining Western CPE, Jessica was the acting CEO and managing director of public policy of a national organization for accountants where she was instrumental in leading the organization’s nonpartisan policy agendas, education, and advocacy efforts.

Jessica holds a J.D., cum laude, from the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law and a B.S. from the University of Maryland, College Park.